From XTC’s Nigel to Wall of Voodoo’s Factory, how ’80s bands turned work, capitalism, and control into unforgettable songs.

Work was everywhere in new wave music — or at least the dread of it. The factory job you didn’t want, the cubicle that crushed you, the humiliating boss. Some bands sneered, some danced, some just got absurd about it.

But these weren’t just artful gripes. They came out of the Reagan/Thatcher years, when unemployment was high, inflation was punishing, and industries were collapsing. Factories closed across Britain and the American Midwest, while privatization and “greed is good” capitalism reigned. For a whole generation, work didn’t mean self-actualization — it meant drudgery, fear, or escape. Against that backdrop, new wave turned the job into the hook, the punchline, and sometimes the monster rising out of the water.

XTC were a cult favorite in new wave music circles. They were known for their razor-sharp wit and the new wave sonic edge to deliver it. They could even make a song about new wave music itself a confrontation (This is Pop?).

Making Plans for Nigel is a fan favorite. It works as a tale of overbearing parents imposing a factory job on their son, regardless of his passions or aptitudes. Surface-level approval from Nigel is conveniently taken as the gospel. They like that Nigel (at least feigns) to be extroverted yet obedient. Poor Nigel — but really, poor society. The sarcasm stings because so many kids were still being funneled into ‘respectable’ jobs or family businesses. This 1979 single was released in the midst of a spate of UK factory closures. The resulting unemployment made the “factory job destiny” feel particularly bleak, so I’d imagine that teenagers and young adults listening in caught Partridge’s sarcasm easier than otherwise.

Devo was formed around the concept that society is warping, or de-evolutionizing people. Mongoloid directly references this. Also, they prefaced their sophomore album with a Devo Corporate Anthem. They sucked the humanity from a Mick Jagger-sung track in Satisfaction, which was no easy task. Could they combine these two elements?

Enter Working in the Coal Mine, which was a mid-60s New Orleans-style R&B song that was a top-10 hit in the US. Like Tainted Love, Devo zapped it with the new wave freeze ray — ironic, since Akron was about rubber factories, not coal mines. In Dorsey’s original, despite being a bit tongue-in-cheek (the album cover has him smiling with a pick-axe), you feel the coal miner’s pain. But in line with their nihilistic stance, Devo brilliantly twisted Coal Mine into an allegory of labor as dehumanization. The mine/factory mismatch? Devo took care of that. For instance, Dorsey’s coal mine percussion was replaced with antiseptic, heavy machine-like synths. Furthermore, elements of the R&B original were emotionally flattened, and others were exaggerated to cartoonish effect (the complaint “How long can this go on?" “whoop!”).

Sure, Devo are the new wave gods of nihilism, but Wall of Voodoo ain’t no slouch either. Whether it be the self-inflicted wounds of Lost Weekend or the “what was the point?” questioning in Call of the West, Ridgway and company delivered the pathos. Their droning track Factory is another shining example. Stan Ridgway later satirized corporate life with Piledriver and I Wanna Be a Boss, but it all started with 1981’s Factory.

At over five minutes, the song itself feels endless — which is the point. Ridgway is painting a picture of the factory as monotonous and never having to rest. The lyrics have a Devo-style nihilism and absurdity to them, but are deeply personal rather than clinical. Ridgway plays the role of a longtime factory worker. Eating the same chicken lunch every day is monotonous, like the factory itself. But he also brutally describes workplace hazards (noxious gas killing his memory and a saw cutting off his thumb). Then in an absurd turn he keeps complaining the thumb stub itches. The guitars and synths keep chugging along, keeping in line with the song title and lyrics. The result is a song that feels endless, the musical equivalent of punching a clock that never stops ticking.

The Jam, like their peers the Specials and English Beat, often called out societal strife. But the Jam did it grace of a sledgehammer. I’ve got nothing against that, especially since their vivid lyrics and great vocal dynamics and timing make their execution effective. Case in point: the sarcastic urban blight tale of That’s Entertainment.

Now I wasn’t familiar with the Jam’s Smither-Jones but there’s a lot to like about it. Sonically it echoes the Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby with its baroque string arrangement. While Paul Weller will never be mistaken for Paul McCartney, his vocals are also somewhat restrained until letting loose toward the end. Good curveball! Lyrically, the Jam, as expected, eschews metaphors and opts for the straight-forward and scathing. For example, “work your arse off” and “packed like tinned sardines” Visceral impact aside, it also works as a rich narrative. A vivid picture is painted of Smithers-Jones as a cog in the corporate machine, then he’s thanked for his hard efforts with a pink slip.

And I have to mention this: I kept thinking of the corporate tool Smithers from The Simpsons. Was Groening a fan of the Jam? Either way, Weller’s point lands: even the most diligent company man can be discarded like yesterday’s paper.

The Police had personal songs that resonated deeply. This is thanks to Copeland’s drums, Summers’ angular guitars and Sting’s heart-on-his-sleeve vocals. But they could “fight the power” too, like with the early, confrontational track Dead-End Job.

But flash forward to the Synchronicity album, and the Police had evolved well past “This job sucks!". Indeed, Synchronicity II shines with its sharper corporate critique. The anxiety-provoking synths and Sting’s wailing in the intro set the tone well. The song begins with a tense weekday family breakfast, with Sting playing a child narrator. Sting then colorfully describes the ills of corporate life: pollution, labor exploitation, and the objectification of women. Regarding the dad, “Every meeting with a so-called superior is a humiliating kick in the crotch” is one of the most withering new wave lyrics I ever heard. You really think he’s one step away from going full Clark Griswold (Christmas Vacation era).

To tie all this together, Sting keeps referencing the Lochness monster rising and coming out of the water. My guess is that, as Godzilla emerged from the water and rampaged Tokyo in response to radiation, this monster will do the same to London because of the woes of industrialization. The monster is metaphor, but the misery is real — the daily grind threatening to erupt into something uncontainable.

The early incarnation of the Human League had some funeral-toned songs (their cover of You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling). But sowing anxiety was also in their wheelhouse. In Dreams of Leaving Oakey plays a character who’s afraid of having a bad reputation in their office and maybe even losing his job. His anxiety is so intense he equates the workday with battles in a war (“our lives will be in danger”, “they won’t let us reach the border”). There’s some PTSD involved as he fled his wartorn or fascist homeland (maybe behind the Iron Curtain?) for England. But the line “I thought things would be better… I find I’m still resented” shows his disdain for the office life. He once again has dreams of leaving.

As for the music, it’s cold, like you’d expect from early synthpop. But the League are deft enough with the synth to induce a disconnected-yet-uneasy feeling. Warbling effects are key to this result. But it’s also the extended silences that keep you on the edge. In the end, it’s less a song about escape than about the gnawing realization that work and exile can feel like the same thing.

The Human League debuted in 1979 as a gloomy synthpop outfit in the vein of Kraftwerk. After two albums they broke into two: The incarnation of the Human League most people know (core of Oakey, Cathrall and Sulley), and Heaven 17. Both became sonically more accessible, but Heaven 17 more often went political (debuting boldy with We Don’t Need This Fascist Groove Thang).

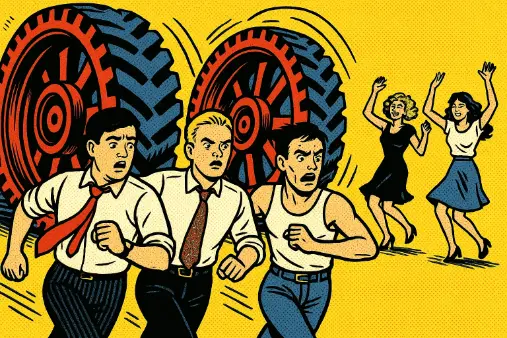

But Crushed by the Wheels of Industry is the epitome of sarcastic music. Sure, many bands will wrap a gloomy song with an upbeat melody, but half the lyrics in Industry are positive, only to be crushed by the chorus. Even the triumphant ‘ooo-ooo!’ is undercut by harsh metallic crashes — a little on the nose, but effective. As for the music, it’s infectious and danceable synthpop (it was a dance hit in the US). As with other Heaven 17 songs, Industry has elements of funk and an extended bridge. Vocalist Marsh has a lot to say in the verses but hammers them home with the simple chorus.

The Talking Heads made songs that could peer into people’s souls, whether it be the twitchy Psycho Killer or the mid-life crisis of Once in a Lifetime. They would rarely get overtly political like XTC or Heaven 17. But they didn’t ignore macro-level malaise.

On the surface, Found a Job is just about bad TV — but really it’s a metaphor for abandoning the corporate grind. In it, people are complaining about poor-quality TV shows, and Byrne is pushing them to make their own shows in response (even before the Internet!). But actually, Found a Job is a metaphor for abandoning the corporate and factory grinds and do work that is more creative and self-actualizing. Byrne is genius at returning to the TV example (“there might even be a spin-off”, “inventing situations” and “scouting locations”).

I think of Found a Job as a proto-Nothing But Flowers. It criticizes society but the focus is on the solution and we see things improve in real time. It’s that rare case where new wave treats work not as drudgery but as liberation — making art your job instead of consuming someone else’s.

Four decades on, the workplace anxieties in these songs still ring uncomfortably true. Factories may have given way to laptops, but the themes are familiar: conformity, burnout, layoffs, meaningless meetings. Heaven 17’s sarcasm, XTC’s parental pressure, or Wall of Voodoo’s droning factory shift could just as easily soundtrack the gig economy, AI fears, or corporate Zoom fatigue. New wave didn’t just capture its own moment of Thatcherite capitalism and industrial decline — it nailed something timeless about labor itself. Work remains absurd, soul-crushing, and sometimes darkly funny. Which makes these songs not period pieces, but work anthems that never clock out.