Intro

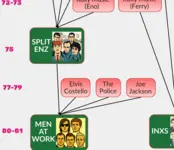

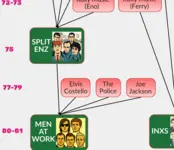

New wave wasn’t just all sharp angles and catchy hooks — it was a genre that thrived on contrast and complexity. And while ethnic minorities have long been well represented across popular music, their stories within New Wave are often overlooked. In this article, we spotlight four artists whose cultural identities helped shape their lyrics, sound, and personas. From post-punk to art-pop, their outsider experiences added depth to a genre already defined by pushing boundaries and breaking molds.

Explore the Synth & Swagger Members' Editions

Adam Ant vs the Media, Canadian New Wave, Female Empowerment in New Wave

And a new enhanced article every month

Adam Ant (Romani grandfather)

During their heyday, Adam and the Ants were a lot of fun, with party anthems like Antmusic. But behind this was a deeper side to Adam Ant (well before Wonderful). Adam Ant remembered stories from his Romani grandfather about facing discrimination in Europe — a legacy that fueled his fascination with nomadic identity and tribal themes. Ant acknowledged these stories and struggles gave him a fascination with nomadic identity and tribal themes. Feeling like an outsider himself, Ant channeled this into lyrics and sounds drawn from Native American and African influences.

Kings of the Wild Frontier is the lead single, title track and opening track of the new look Ants (after ex-Sex Pistols manager Malcolm Mclaren stole his original Ants to form Bow Wow Wow). It serves as a great introduction to both Adam’s bravado and fascination with outsiders. The phrase “A new royal family, a wild nobility” covers both. There’s also the Ants’ signature “Burundi Beat”, influenced from African drumming. Ant’s vocals and Marco Pirroni’s guitars resemble a native American chant.

The Human Beings might be light on lyrics; it’s mostly the repeating of the names of several Native American tribes. But Adam Ant, with the repetition and song title, is sending a powerful message that Native Americans (and by extension the Romani) are human beings, despite their treatment otherwise at the hands of the Europeans and Americans. Their Burundi beat and other musical elements are still there, just slowed down and driving home Ant’s mantra.

Lene Lovich (Serbian-American who moved to the UK)

Lili-Marlene Premilovich (Lene Lovich) was born in Detroit to a Serbian-American father and British-American mother. When she was a teenager her mom moved them to her native UK when her dad fell ill. Lovich’s outsider perspective shaped her melodies, which often draw on Balkan instrumentation and vocal techniques passed down from her father. And there’s often a surreal, “I’m here but I’m not” quality to her music. The lyrics often speak of celebrating quirkiness. Her wardrobe had a street-performer’s Eastern European flair, and her stage persona was part circus act, part mystic. (She’s even coming to Chicago soon—can’t wait.)

Lovich’s song Home is the best encapsulation of her complicated, perhaps painful childhood. The verses are mostly negative adjectives for home (or childhood), like “close control”, “suspicious” and “good, clean living” (control freaks?). Then the line “I forgot” followed by “let’s go to your place” shows Lovich coping with the memories she just dredged up via avoidance. The musical accompaniment is sparse to begin with (just a guitar). This is done to lay bare her pain. Only then do the organs, drums and other instruments then join the fray.

Sleeping Beauty is a great homage to Lovich’s Balkan heritage. For starters, the waltz time signature is a favorite in Balkan folk music, as are the violins and clarinets. Being a new waver, Lovich reaches for the synths, but they are warbly and compressed. They’re raw like a street performance, rather than the antiseptic synths of the Human League. Her fast shifts between lullaby and declaration are similar to a Balkan singer delivering a fable.

Other Eastern-European new wavers: Ivan Doroschuk (Men Without Hats), Nina Hagen

Lynval Golding and Neville Staples (Jamaican-Brits)

Golding and Staples were both born in Jamaica. There, Golding played guitar in mixed-race bands, making him an eventual natural for bridging new wave and Jamaican rhythms. Staples was immersed in ska, rocksteady and reggae, all of which influenced the Specials. Both moved to towns in the UK during their childhood, and eventually met each other in Coventry. As Black youths in the UK, they faced displacement, street violence, and police hostility. As members of the Specials and Fun Boy Three, their songs often touched on racial themes, with Margaret Thatcher sometimes the antagonist. Swap out Thatcher and company for the villain de jour and their work still resonates.

Ghost Town is the Specials’ most well-known song and through eerie instrumentation and concise words describes urban decay in the UK. At the turn of the ‘80s, rioting was rampant in the UK, particularly hitting black communities such as the ones Golding and Staples grew up in.

Golding wrote the B-side Why? after being assaulted by a white man, foreshadowing a brutal real-life stabbing the following year. There are references to the British Movement and National Front (a neo-Nazi group and far-right political party). The American Ku Klux Klan is also mentioned. Unfortunately the song was prophetic as Golding was stabbed in the neck the following year. Musically, Why? is a great example of Staples toasting, a staple of Jamaican sound system culture.

Other black new wavers: Ranking Roger (The Beat/General Public), Poly Styrene (X-Ray Spex)

Johnny “Vatos” Hernandez (Mexican-American)

Danny Elfman from Oingo may get the limelight, but Johnny “Vatos” Hernandez deserves some time too. Hernandez was born and grew up in the Chicano neighborhood of East Los Angeles, which was a core part of his identity. Though Elfman led the band creatively, the death masks and skeleton motifs echoed Día de los Muertos — a natural fit with Hernandez’s heritage.

As Boingo’s long-time drummer, Hernandez did more than keep time — he gave shape to the chaos, bringing precision, swing, and Latin pulse to the band's most kinetic tracks. His later solo projects and Day of the Dead concerts made the connection explicit, reclaiming that Boingo aesthetic through a Chicano cultural lens. Hernandez often spoke out on representing Chicano culture in the mostly-white new wave scene. He’s also walked the walk - founding local youth drumming programs and has being a fixture at East LA art festivals celebrating Chicano identity.

Latin rhythms in Boingo’s music are quite prevalent in Who Do You Want To Be?. Hernandez’s drumming is in the style of the timbale (a Latin-style drum) and is heavily syncopated. That and the punchy horn lines are reminiscent of Latin dance music. Of course, filtered through Boingo’s signature mix of mischief and menace and grounded by Hernandez’s percussive vision. Cinderella Undercover blends Hernandez’s rapid-fire Latin-inspired drumming and punchy horns with sudden pivots into off-kilter punk - classic new wave alchemy! Gratitude is slower but still has a Hernandez-vibe. It’s centered around a driving percussion line with congas and hand drums, giving the song an almost Santana-vibe. Indeed, the groove complexity shows Hernandez’ Latin roots. Finally, the Dead Man’s Party album cover — with its skeletal mariachi figures—and the music video’s vivid, Día de los Muertos-like visuals reflect Oingo Boingo’s macabre whimsy, but also echo Chicano cultural motifs. Hernandez’s heritage gave these deathly celebrations a deeper cultural resonance.

Other Hispanic new wavers: Joe “King” Carrasco”, Andy Prieboy (Wall of Voodoo)

Outro

In a genre built on artifice and reinvention, these artists brought something real: identity forged from migration, resistance, and resilience. Their backgrounds didn’t just color the music—they gave it its tension, fire, and edge. If new wave is a mosaic, these stories are essential tiles. They prove that behind every synth line or tribal beat, there’s often a deeper rhythm—one that echoes with family, heritage, and the outsider’s drive to be seen and heard.

Adam Ant vs the Media, Canadian New Wave, Female Empowerment in New Wave

And a new enhanced article every month