Intro

Thomas Dolby’s catalog is way more diverse than people remember. He didn’t just dabble in quirky synthpop — he built entire worlds with romance, satire, and sorrow. Across his first four albums, you’ll enjoy his experiments with funk, ballads, jazz, and even a sci-fi noir or two. But forget the lab coat for a minute. There’s a lot more to Dolby than whatever that one hit was called again…

Explore the Synth & Swagger Members' Editions

Adam Ant vs the Media, Canadian New Wave, Female Empowerment in New Wave

And a new enhanced article every month

Golden Age of Wireless

The Golden Age of Wireless is nothing short of a synthpop gem. While Gary Numan and early Human League were icy, Dolby was part of (or maybe started) a wave of warmer synthpop with heart (a bit before Eurythmics made this shift). Even the album cover has humanity: it’s full of tubes and wires but you’re still drawn to Dolby. The track Windpower literally asks you to “switch off the mind and let the heart decide. In Radio Silence, Dolby’s dynamic lead vocals and the female backups voices squashes any coldness that the synths and vocoders might sound like otherwise. The lyrics are deep as any ocean but the melodies are still catchy and bright (I love that duality). Indeed, the songs can be enjoyed on two levels: as ear candy or for deep listening.

Europa and the Pirate Twins

Europa hooks you right away with its fast rhythm and bright synths. The verses have mellow vocals and melody which allow for better focus on the complex lyrics. It’s also a great setup for and contrast from a particularly strong chorus. Dolby both triumphantly sings and whispers in these dynamic choruses. The catchy synth and rapid drum machine hits add to the catchiness of it all. This allows for better focus on the complex lyrics. While the song is on the surface about Dolby pining for someone named Europa, I think the song also works as a Cold War allegory. Europa is caught in a tug of war between the US and Soviets, more alike than they admit to because of their aggressive, pirate nature. Even early on, Dolby’s lyrics were open to interpretation but not too cryptic.

The Flat Earth

In my article about Duran Duran's Sophomore Leap, I said Dolby fell flat commercially with Flat Earth. I once thought he stumbled—but now I hear intention in every detour. Besides Hyperactive (which is funky and lives up to its title), Dolby decided to go experimental with Flat Earth. And while Flat Earth is still mostly synthpop, Dolby fires his freezeray on it. The synths are colder, and the lyrics aloof. Dissidents has synths that make you a little uncomfortable rather than warm. That being said, Dolby doesn’t lose his lyrical twists and turns (“My writing is an iron fist, In a glove full of vaseline, dip the fuse in the kerosene”). Mulu the Rain Forest deviates that most from that Golden Age sound, with a strong emphasis on texture rather than hooks.

White City

While I would find 37 minutes of songs like Hyperactive stressful, there are some songs on Flat Earth are meandering and hookless. White City is a great middle ground. It has a catchy melody while still expanding his sound from Golden Age and going deep lyrically. The synths are tense and sleek, and there’s a noir feel to the song that foreshadows dangerous lyrics ahead. A bit of guitar crunchiness in the bridge is a good deviation, giving the song life. Dolby’s vocals are more urgent than usual, but its nice that it doesn’t veer into anger.

The lyrics to White City are complex and ambiguous, even more so than Golden Age. I interpreted them as a drug lord’s negative impact on everything around him. For example, the line “you’d never rest till we’re all incinerated and you know you’re the best” bring to mind fellow drug lord Walter White of Breaking Bad fame.

Aliens Ate My Buick

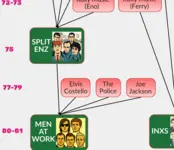

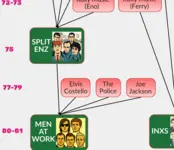

Dolby took a break from recording after 1984’s Flat Earth. And in between, new wave artists started to shift sonically. For example, Sting and Stan Ridgway broke off from the Police and Wall of Voodoo to make albums with jazzy and western motifs. Similarly, with Aliens, Dolby shifted more from pure synthpop. Compared to Flat Earth, Aliens is more eclectic sonically and lyrically. The over-the-top funk caricature of Hot Sauce is a highlight. And Airhead is sonically upbeat but cranks the sarcasm and wit from Sparks to Pet Shop Boys. Lyrically it’s an impressive album. The B-side is a lot more chill, like Flat Earth, but keeps the variety and improved writing (for example, the tongue-in-cheek reggae-tinged My Brain is Like a Sieve.

The Key to Her Ferrari

The Key to Her Ferrari is the album opener and has Dolby making a complete 180 from the delicate and atmospheric Flat Earth. Robin Leach starts it off with a spoken word part, and then a lounge song wrapped in chaos ensues. A loungy, kitschy synth plays throughout, especially in the long intro. But its twisted, punctuated by intense drum hits. Later keyboards and guitars join the mix. In the song, Dolby shows off his lyrical prowess. The Ferrari in question is a thin veil for a pursuit, foreplay and sex, complete with Freudian slips like “phallic symbol on wheels” and “I thought of my mother”. Dolby employs vocal theatrics, such as shifting from crooning to shouting and back. This excitement serves to highlight the absurdity and sexual innuendo. You’re sold that he’s obsessively pursuing a woman, kissing her and such (“kicking those 500 Italian horses to life”), and climaxing (“As we hit 100 my love exploded”). As an aside, Dolby doubles down on the retro by having Laura Creamer (of ‘60s girl group fame) as backup vocalist.

Astronauts and Heretics

Flash forward to the early ‘90s, and the music scene is a lot different. Synths are out and guitars are in. And while some artists went acoustic to survive and others withered with their synths, Astronauts and Heretics shows Dolby finding a great middle ground. Overall its still synthy, but guitars are judiciously added. Musically its all over the map, but it works! Whether it be the Cajun flavor of I Love You Goodbye, the tear-jerking I Live in a Suitcase, or the stark minimalism of Cruel. Energywise its consistent compared to Aliens, staying mostly in the middle.

Close But No Cigar

Close But No Cigar is a standout track, and highlights Dolby’s sonic shift with Astronauts. The guitar in the opening riff and elsewhere sounded familiar to me. Dolby’s the ultimate collaborator, and used his technology and science know-how to help Eddie Van Halen with his sound machinery. In return Eddie laid down his signature guitars for Cigar (and the Europa sequel Eastern Bloc). While Dolby is not an intense vocalist, he’s more emotionally raw here.

The lyrics are poetry in motion: heartfelt (“I must have been lonely”), tongue-in-cheek (the title) and subversive (“It’s more like my love gone wrong song”). The genius of these lyrics line in Dolby’s balance of tones without them collapsing on each other. Like the Human League’s Don’t You Want Me, Cigar is a musical argument. The two choruses switch between Dolby and his love interest. And Cigar serves as the perfect anthem for gracefully losing with flair, and I even thought of it when losing a paddleball match or other low-stakes setback.

Outro

Dolby’s early albums make a strong case that he was never just a novelty act or a synth wizard with wild hair. Whether crooning over heartbreak, snarling through satire, or collaborating with guitar gods, he delivered songs that still feel oddly ahead of their time. So next time someone brings up that song—you know, the one that blinds you with…something—send them here instead. The real story’s in the albums, not just the sound effects.

Adam Ant vs the Media, Canadian New Wave, Female Empowerment in New Wave

And a new enhanced article every month